When Wendy Stephens launched a digital library at Buckhorn High School in New Market, AL, the school librarian turned to the classics—and didn’t spend a penny on one. Instead, she’s created a schoolwide ebook collection comprised entirely of public domain content.

Buckhorn High School student Floyd Gaines reads a Project Gutenberg copy of Jonathan Swift’s 1729 essay, A Modest Proposal, on his own iPad

“If I invest in a book, I’d rather have the physical copy and know I have it, rather than buy a subscription model and not know if I’d be able to have the money next year to renew the subscription,” says Stephens. “I made the decision that had the biggest economical impact.”

That meant diverting some funds earmarked for classroom books to technology and spending $7,000 on 25 Nook Simple Touch ereaders for a freshman English class, along with additional devices for the library. No, students can’t download The Hunger Games, but there’s plenty of digital content available, from Google’s free ebooks to the material on Project Gutenberg. Students just have to ask. They can also request ebooks through Buckhorn’s website, fill out an online request form, and have the library download the material for them.

Beyond expanding the ebook collection, the new digital policy is opening other doors at Buckhorn. In the elective English course “The Novel,” for example, students often had to pay for their own books. The Nook helps alleviate what was a hardship for some students, who might have been discouraged from taking the class due to the cost. Furthermore, as more kids are exposed to the devices, their experiences are initiating conversations about working with digital content.

“One student came to me and said they found The Great Gatsby in the public domain in Australia,” says Stephens, who adds that F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic is still copyrighted in theU.S.(Plus, the Australian version was in HTML and not formatted for the Nook.) “And so we also talk to students about piracy and copyright.”

As the use of digital content grows in schools, school librarians are making decisions on how to best acquire this material. In some cases, they’re choosing to spend money on ereaders and lean toward free content. Others are leveraging the personal devices of students and teachers and putting their funds into subscription-based models. But the goal is the same—to grant students and educators access to digital content.

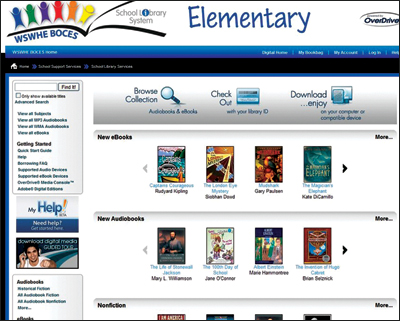

Paige Jaeger didn’t launch the ebook library that serves 84 regional school libraries and 32 school districts of the Washington-Saratoga-Warren-Hamilton-Essex Board of Cooperative Educational Services (WSWHE BOCES) inNew York. But for the past four years, Jaeger, WSWHE BOCES’ coordinator of school library services, has shepherded its growth by choosing to spend her budget on content, rather than devices.

Working with digital content distributor OverDrive, WSWHE BOCES has spent about $20,000 for 1,000 titles, from 2007 through this year. These range from multiple copies of a popular title to audiobooks, which can run up to $50 each. The ebook collection has seen demand blossom from just 300 checkouts systemwide a few years ago to about 3,000 in the 2010/2011 school year. (Students don’t always follow through with downloading a book after checking it out.).

Users can also access the material by walking into the library to download ebooks onto their devices or by logging in from home. To serve younger kids, Jaeger has launched an elementary school digital library just this year.

“We didn’t want elementary school children walking in with iPhones just as we wouldn’t have them co-mingle in a young adult section of the library,” says Jaeger, who feels that young students shouldn’t have unlimited access to all material in the ebook library. As in a bricks-and-mortar media center, they should be guided to certain virtual areas online, she says.

And as all 32 school districts contribute funds that include supporting the digital collection, the cost of the OverDrive library ends up being about 25 percent of what each district would have to spend independently. Currently, about 75 percent of the school libraries use the collection, with some, about 30 percent, allowing students to access the material over WiFi in the library, and 10 percent offering wireless schoolwide. Students can use Web 2.0 tools, do research over their own devices, and, of course, download and read books.

At Buckhorn, digital adoption is occurring at a slower pace, but Stephens is watching with interest as the school continues with its own ebook initiative and ereader adoption. Some students love the Nook, while others still read paperback versions of their assigned material, using the Nook for keyword searches.

A few students have had a “violent reaction” to the device, saying the Nook hurts their eyes, according to Stephens. Overall though, she believes the devices are having a positive influence on student learning and teaching—and she plans to purchase another set of 25 Nooks when the new fiscal year begins later this fall.

“One of my least favorite annual assignments was a page of quotes from Wuthering Heights, where the kids had to read through and note the page number where it appeared,” says Stephens. “But with the Nook, they can easily search keywords and find the answer, so that assignment changed. So I think it’s having a positive affect on instruction as well.”

[…] Ebook Collections: Two Stories Two different approaches to acquiring and supplying ebooks Source: http://www.thedigitalshift.com […]