(This story has been updated to include comments from the New York Public Library.)

One year ago, when HarperCollins Publishers implemented its 26-loan cap for library ebook lending, the new policy brought down upon the publishing house all the thunder that the library world could conjure — from petitions to boycotts.

But over the past year, as the library market has been further roiled, as other companies, such as Penguin Group, essentially stepped back from the market altogether, HarperCollins has remained not only committed to its model but also to the market. And for this, it is receiving from some librarians, if not praise, at least a sober reappraisal — even from some of those who are holding firm to their boycott.

“Librarians’ passionate advocacy of our titles is vital to our efforts and we remain committed to keeping our ebooks available in the library channel,” said Josh Marwell, Harper’s president of sales.

Marwell said that the 26-loan cap remains a work in progress, but no other business model has emerged in the past year that makes more sense to the company.

“We still think our decision was the right one because it fulfills our goal of continuing to make ebooks available to libraries at the same time speaking to our concern about how increasingly frictionless library borrowing could affect the emerging ebook ecosystem,” he said.

The Columbus Metropolitan Library (CML) in Ohio was not among the libraries that decided to boycott HarperCollins, and the Harper licensing model has not been an issue there.

“We have had no problems to date – smooth sailing,” said Robin Nesbitt, the technical services director for CML. “I’m not sure we’ve even hit the cap – so for all of the hand wringing out there, we have been just fine,” she said.

The Municipal Library Consortium of St. Louis County (MLC), which consists of nine independent community libraries in Missouri, has now changed its mind about the boycott it approved last year.

“A couple of months ago we started purchasing from them again,” said Tom Cooper, the consortium’s president and the director of the Webster Groves Public Library. “The reality on the ground is that it’s more generous than what we are getting from other publishers,” he said.

Anne Silvers Lee, the chief of the materials management division at the Free Library of Philadelphia, said she did not think they had yet hit the 26-use limit for any of their HarperCollins titles, but she wasn’t completely sure.

“The biggest issue for us with the HarperCollins licensing model continues to be figuring out where we are in the count,” Lee said. “I don’t know if the problem lies in how OverDrive is implementing this or if it’s because HarperCollins has asked that this be managed in a certain way,” she said.

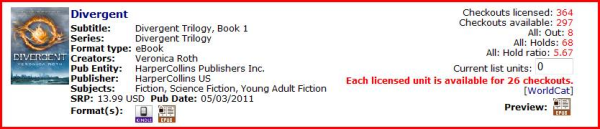

For example, the illustration shown here for a Harper’s title, provided by Ted Bohaczuk, the orders librarian in Philadelphia, indicates there are 364 checkouts licensed, which translates to 14 copies (364 divided by 26). There are 68 holds, which is a hold ratio of 4.86 (68 divided by 14). But the displayed hold ratio is 5.67.

“5.67 would be the ratio if we had 12 copies. Have 2 copies been exhausted? I don’t know of any way to tell,” Lee said.

While this is a nuisance, Lee said she was “professionally pleased and relieved” that HarperCollins continues to partner with libraries.

“They’ve opted for this route while Random House has decided to increase prices,” Lee said. “But both companies have effectively signaled their continued commitment to doing business with us,” she said.

The New York Public Library has 5,120 HarperCollins titles in its e-collection, and, to date, none have exceeded the 26-loan cap, according to Miriam Tuliao, the assistant director, central collection development.

“Although the policy change slightly affected our ordering process, it did not alter our mission,” Tuliao said. “And we have greatly appreciated the broad variety of titles, both backlist and new, that we have been able to offer our patrons,” she said.

“Just this week, someone from the group emailed whether we want to revisit the boycott because so many aren’t willing to sell at all,” she said.

Others who are still boycotting, such as the North Texas Library Partners consortium, are more willing to make a nod in HarperCollins direction.

“Our consortium is frustrated with the availability of best-selling titles and would prefer a HarperCollins model over no availability of titles,” said Carolyn Brewer, the consortium’s assistant director, adding that when titles aren’t available it gives libraries an unjustified black eye.

“We probably are a little bit more understanding of their loan cap, even if we still are not sure we agree with the number 26, but we understand there may need to be some caps so [it’s more fair] to authors and publishers,” she said.

Marwell said that HarperCollins has been working with distributors to ensure libraries receive sufficient notification of titles with low remaining circulations, and, in addition to running ebook promotions for libraries and meeting with librarians, the company has signed on with other companies now offering ebook platforms, such as 3M and Baker & Taylor.

The objections over the past year have not gone unnoticed, Marwell said.

“It was good to be reminded of how strong a voice libraries have in the national life,” Marwell said.

But a number of librarians said the model still does not work for them.

“A lot of people have said the fact that they are willing to sell is better than those that won’t, but it’s always been a little bit more about the principle here,” said Timothy Burke, the executive director of the Upper Hudson Library System which does not lease electronic titles from HarperCollins. “We want to create a model that will work for everybody, and I know the American Library Association has been doing some good work in this area and having conversations at the highest level,” he said, referring to the ALA contingent that met last month with Macmillan, Simon&Schuster, Penguin, Random House, and Perseus publishers.

Burke said his system will have a contingent at the Public Library Association’s conference next month in Philadelphia, and that they intend to talk to publishers and OverDrive about what can be done to improve the situation.

“We understand the publishers are looking for a way to come up with a model that works for them, and libraries are willing to work toward that,” he said.

Iowa’s WILBOR consortium, the Nebraska OverDrive Libraries, the Kewanee Public Library, the the Central/Western Massachusetts Automated Resource Sharing consortium (C/W Mars), all are maintaining their boycott.

“We do have it in place. I don’t know how much good it’s doing because I don’t see them changing their position,” said Joan Kuklinski, the executive director of C/W Mars, which was one of the first organizations to boycott. “I’m watching with interest ALA”s effort to establish a dialog with vendors and publishers and hoping something comes out of that,” she said.

I implore you, fellow librarians, don’t capitulate! I think we should use the outrage and unity against Penguin to re/establish a HarperCollins boycott. Jessamyn at librarian.net made a flyer for libraries to inform and engage patrons in the fight against MacMillan, Hachette, Simon & Schuster, Penguin and Brilliance.

Despite the cuts, we still hold a lot of collective power. If we show the companies our strength now, they’ll think twice about pulling tricks later. Let’s learn from the Union Protests in Wisconsin.

I hate to say it, but If we wimp out, we’re the ones to blame.

R.L. Dee:

It is good to hear some outrage amidst all the wimping out, from the ALA on down. To say that the HarperCollins policy is acceptable by comparing it to publishers who won’t even sell to libraries is wimping out in extremis. It is a pity there is no platform from which we can launch real collective action.

I have been warning about the commercializing of eBook lending and the threat it poses to public libraries since last October, and the situation has only gotten worse since then. Amazon’s lending program was bad enough, but now Bilbary is looming on the horizon, apparently an intended Amazon killer that has the support of Big Six publishers and 2,300 others. If the lending component they are threatening to implement becomes a reality this spring, two commercial eBook lending venues will be out there, taking libraries further out of the loop. If we don’t act soon, our patrons, who demand eBooks, will be off to greener pastures in droves.

The End of Libraries

http://alltogethernow.org/showtag.php?currid=85

Just a friendly correction, I publicized the flyer but it was made by Sarah Houghton, the Librarian in Black. Here’s a link to her original post.

http://librarianinblack.net/librarianinblack/2012/02/ebooksign.html

I am at a loss as to why there would be a cap on eBooks. There isn’t a cap on print books so why are eBooks so different? If a library purchases a copy of a book they are free to loan that book out as many time as they want. An e-Book should be exactly the same. There is no loss of revenue to the publishing house/author. They receive the same payment that they would receive for a print copy. There is little to no difference in pricing between eBooks and print books. Yet for some reason there are restrictions in eBooks. With a print book if I no longer wish to own it I can re-sell it, trade it, or donate it to a library/prison program/literacy program, etc. I can not do that with an e-Book. On top of that if the company “selling” the e-Book (e.g. Amazon) goes out of business or loses it’s right to distribute the eBook I will lose my access as well. The publishing houses are making a killing. We are no longer buying a product but rather are buying a usage of a product for as long as the publisher cares to allows us to do so. This is an outrage and more people should be protesting this, not just libraries!

Marlena,

I share your outrage, as you can see in an above comment. Let me correct you, however. There IS a difference in pricing between eBooks and print books. eBooks typically cost libraries MUCH more than print books, if publishers are willing to sell them at all. Prices for a book a library might pay $12-15 for in print can run them up to $100. Some publishers, even at that price, won’t sell libraries more than one copy; three of the Big Six won’t sell to them at all.

HarperCollins’s cap, though set too low at 26 checkouts, is understandable. Popular print copies wear out and have to be replaced over time. eBooks do not.

Access issues can be complicated. However, purchases that download to your reading device are pretty securely yours. Loans from libraries or a commercial lender do disappear after the loan period.

The End of Libraries

http://alltogethernow.org/showtag.php?currid=85