Espresso Book Machines tie self-publishing to Maker culture

The Makings of

Maker Spaces

-

Part 1 — Space for Creation, Not Just Consumption

-

Part 2 — Espress Yourself

-

Part 3 — A Fabulous Home for Cocreation

In his presentation at the 2012 Computers in Libraries conference, Fiacre O’Duinn defined Maker culture as “learning through hands-on creation; a combination of technology, art, and citizen science; and a sharing of results and, often, process.” Whether its via 3-D printers, microcontrollers, knitting, or gardening, Makers want to shape everyday objects to be reflections of themselves, not have their identities be made up of the objects they use.

Over the past 40 years, public libraries have followed popular culture through the ever-more-abstract artifacts of the digital age, offering music and video in every format, public computers for Internet access, online branches, and downloadable content. Now, some libraries are following Maker culture back to things we can hold in our hands.

One unexpected tool in this return to the physical is the Espresso Book Machine from On Demand Books. This mobile printing factory is a high-output photocopier coupled with a book-binding robot, able to produce quality paperback books in about five minutes—just long enough to go get an espresso while you wait.

Join us for the

LJ Tech Summit

An Online Event

November 14, 2012

11:00 am – 4:00 pm EST

Discover the tools you need to make the latest technology systems work for your library!

Register today!

Espresso Book Machines can offer two kinds of services: print-on-demand of any title available through the EspressNet database (which includes Google Books, the Internet Archive, all of Ingram’s partnered publishers, and more) and self-publishing services for authors and small publishers.

While the machines have been predictably popular with independent and university booksellers and academic libraries, only four public libraries in the United States have book machines: the Temecula Public Library, part of the Riverside County Library System (RCLS); Sacramento Public Library (SPL), CA; Darien Library, CT; and, most recently, the Brooklyn Public Library (BPL).

What’s been surprising in these public libraries is which book machine service has been more popular and better used. Hint: it’s not the millions of titles available via EspressNet.

One machine, three journeys

After seeing a demonstration of the book machine at an American Library Association (ALA) conference, staff members from RCLS were intrigued by the possible uses in a public library. As Cindy Delanty of RCLS explains, “Our interest was primarily to see how we could improve the speed and lower the cost of an interlibrary loan (ILL) transaction” and find efficiencies in materials purchasing. “We also noted the potential for self-publishing, as an aside,” she continues.

Through a grant from the California State Library, RCLS had its machine up and running early in 2010 as the center of a new service, Flash Books! In addition to printing requested titles, Flash Books! operators also help authors with the self-publishing process. After an initial consultation, the Flash Books! operator will either simply print a finished product (submitted as print-ready PDFs), or help with formatting and cover design for an added fee.

As RCLS evaluated its pilot project, there wasn’t evidence of the ILL or collection development savings for which the library had hoped. Self-publishing, on the other hand, was a huge hit. “We learned right away that self-publishing was more popular and that that use was going to overtake printing,” notes Delanty. Over the past year, RCLS has grown Flash Books! to meet demand, inaugurating a first annual Information Faire and Author Book signing that attracted more than 100 guests and brought in 20 new authors (for a total of 80). “It was the best day of my life,” says Victoria Taylor, Flash Books! operator and coordinator of the information fair.

By contrast, at Sacramento, self-publishing was the primary use of the machine from the start. “We had heard that [the University of California at] Davis was eliminating its creative writing program,” says Rivkah Sass, SPL library director, “and we saw it as an opportunity to take on that role.” Sacramento also used grant funding from the California State Library and the Institute of Museum and Library Services to purchase its book machine and has adopted a fee structure similar to the one used by RCLS for printing and layout/design.

To provide these services, SPL created I Street Press, now staffed by Gerry Ward—a “tech-savvy librarian (who is also a writer)”—and two publishing assistants. The writing classes were taught by former UC-Davis instructors and priced comparably to the college’s courses. However, while free information sessions and short workshops were popular, “people weren’t ready to pay the library for classes,” remarks Sass. I Street Press is currently reevaluating its fee structure for 2013.

At the same time that I Street was starting up, two other libraries were taking a different approach to providing print- and publish-on-demand services. Darien installed its book machine in fall 2011, and BPL received its Espresso in January 2012.

“We have been devising strategies to serve better Brooklyn’s creative community: writers, artists, photographers, coders, artisanal cheese makers, you name it,” explains Richard Reyes-Gavilan, BPL chief librarian. Offering a home for an Espresso Book Machine was one strategy, as is the development of the new Leon Levy Information Commons (opening January 2013), which will contain a laptop-friendly workspace, 21st-century meeting rooms, a recording studio, and a 3-D printer.

Rather than find grant money to purchase an Espresso Book Machine, both Darien and BPL entered into a concession agreement with On Demand Books. Just like adding a library café, “In exchange for a high-visibility space in the lobby of Central Library,” Reyes-Gavilan explains, “On Demand Books pays a base annual commission [and] is responsible for all costs of operation including consumables, support, equipment, and staff.” The author intake process is similar to Flash Books!—an initial appointment and basic formatting help—but the transaction is between the On Demand Books employee and the author.

In all of these libraries, users of the self-publishing service range from single authors to established groups to schoolchildren. Friends groups and other community organizations print custom journals and guidebooks. RCLS has used its machine to print reading journals for summer reading, writing journals for literacy programs, and book journals for book clubs. At I Street Press, it’s been used to publish anthologies for local writing groups and even the Poet Laureate of Sacramento. “Here is Brooklyn” was a creative writing series for third- and fourth-graders this past spring, with printed anthologies for each class.

Espresso and Maker culture

The Espresso Book Machine fails nearly every standard laid out in Make magazine’s Maker’s Bill of Rights. It’s a proprietary device, incapable of running software other than what came with it, and only one company makes it. So far, the most customizable thing about it is the content that goes into it.

That’s where we come back to Maker ideals. A machine that can create a 400-page paperback in five minutes enables an independence from the industrial book publishing process that fits perfectly with Maker culture. The technology isn’t Maker in nature, but the personalization and democratization of the process are.

“Transformative change happens when industries democratize, when they’re ripped from the sole domain of companies, governments, and other institutions and handed over to regular folks,” wrote Chris Anderson in Wired magazine in 2010.

When “regular folks” can cost-effectively print a single book, everything about publishing changes. Small presses and self-publishers, relieved of the need for minimum print runs, can take risks on well-written, important books that never would have been accepted before. Fewer copies of more diverse writing can be produced, and many more voices can be part of our written histories.

A library offering self-publishing services to its community demystifies and makes transparent the creation of a book from idea to physical copy. Using tools like an Espresso Book Machine, libraries can show users that book publishing isn’t just “something that other folks do” but “something that I can do.” People standing nearby watch as a book is printed, fascinated by the machine and asking questions. Everyone understands a little more about how a book comes to be. And at the end, authors walk away with a copy of their book, warm and real in their hands.

Riverside’s Delanty confirms this. “Our machine location has been great. It’s in the public area of the library and is surrounded by glass walls…. Patrons stop by to take a look at the machine regularly. The interest keeps increasing with every new project….” BPL is finding the same effect, proudly displaying its machine among “the great foot traffic” of the Central Library lobby.

However, it may only be a matter of time before the machine itself fits more comfortably into Maker-style use. Victoria Taylor and operators at RCLS have figured out how to insert colored pages manually into the books, and they’re experimenting with adding hard covers after the books are printed.

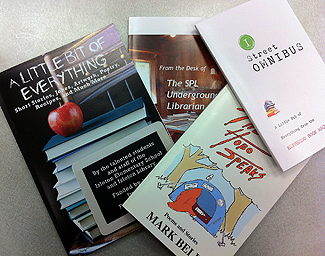

IN-HOUSE PUBLISHING A sampling of titles (inset)

printed by Sacramento PL’s I Street Press.

Photo courtesy of Sacramento Public Library

Public libraries as publishers?

In his new book, The Librarian’s Guide to Micropublishing, Walt Crawford offers an answer. “Public libraries serve lifelong learning, and serve to collect, organize, and preserve the stories that make up our civilization. Micropublishing adds new local voices to that set of stories…. Public libraries already gather the resources to make micropublishing work well and to benefit from its possibilities…. Who better than the library to facilitate [this] process?”

For Sacramento’s Sass, this was the founding principle behind I Street Press. “We truly view the library as the heart of the community and the center of its creative forces. We believe that everyone has a story to tell, and providing the opportunity to tell that story seemed to be a natural role for the library.”

Perhaps, but why spend $125,000–$150,000 on a printing press? Why not host creative writing programs and then use an online service like Lulu.com or Amazon’s CreateSpace for printing, as Crawford suggests in Micropublishing?

As BPL’s Reyes-Gavilan affirms, “Printing your book at the library creates a different relationship between author and library than if you print via a web-based service.” Also, at I Street Press, Sass believes that “Lulu and other on-demand publishers are great options for people who know exactly what they are doing, but…I Street offers a more personal touch, and it keeps the chain, from creative idea to product, local.”

While right now that only works if you happen to be local to a select few locales, that’s already changing: the machine’s price tag won’t stay so high for long. In the past five years, the cost of 3-D printers has fallen to less than $1000; in the next five, the cost of production-quality book printing should do the same. When a book machine costs as little as a MakerBot, many things become possible, even easy.

Putting the pieces together

What about the print-on-demand service? Is the only real value of a book machine in the self-publishing aspect? “To be honest, we do very little POD because the interface to find a title through On Demand Books is very clunky,” remarks Sass. Patrons must search through the On Demand Books site, or use the machine’s on-board computer, to find books of interest. Neither of these search interfaces are as robust as the library’s own online catalog, and there’s no integration between the two systems. As self-published print-on-demand books are added to collections, this lack of visibility will only get worse.

One possible solution was proposed by Chattanooga Public Library’s Nate Hill during his presentation at the South by Southwest conference in March. Hill envisions the entire process, from original idea to finished product, happening within the library. “Public libraries now need to think just as much about supporting the production of knowledge in the community as they do about the consumption of knowledge in the community,” he says.

Hill’s version looks like this: from a library workspace like Brooklyn’s Information Commons or a Library Lab “collaboration station,” an author can log in to the library’s catalog and click on “Create Project.” Instantly, a record is generated with the basics of the author’s idea, and his work is given a library status of “In Progress.”

Using the catalog’s community voting feature, other library users can vote his book up and down, feeling out the potential market for the book and whether it should be added to the library’s collections after it’s complete. There may even be an integrated Kickstarter or Indiegogo campaign to pay printing fees. When the book is finished, the author donates a copy to the library and offers it for sale to the public.

Starting with Hill’s idea, libraries can add in the benefits of a service like Flash Books! or I Street Press. As an author develops her book in library writing and editing workshops, she posts updates and excerpts to the catalog. Once the book is ready to print, the author or the library adds cover art and a better blurb to the catalog record. Through the library’s online catalog, WorldCat, or Google Books, her book is discoverable around the globe; through the EspressNet feature, anyone can print out a copy wherever there’s a machine.

One final aspect of Maker culture can also come into play in a public library: the social and collaborative synergy that happens when creative people come together. As both RCLS and SPL have discovered, some authors need more help than they can provide. SPL currently has a short list of resources in its formatting guide. RCLS, Sacramento, and BPL are all looking to become a place where local creators can connect with one another.

“We want to find people in the community to provide additional help to authors as they design and get their projects print-ready,” says Delanty of RCLS. SPL’s Sass adds, “It’s a giant social media experiment that includes professors, writers, editors, graphic designers, and dilettantes.”

When viewed through the lens of Maker culture ideals, the concept of the public library as micropublisher is an intersection of entrepreneurship and community action. The library can become a gathering place where authors, illustrators, designers, editors, indexers, and researchers can find one another and cocreate great works.

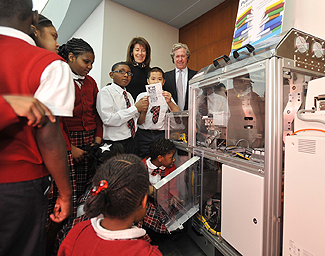

MICROPUBLISHING IN BROOKLYN Students follow each step

of the process served up by Brooklyn PL’s

Espresso Book Machine. Photo ©2012 Phillip Greenberg,

courtesy of Brooklyn Public Library

The library is a growing organism

The ideals behind Maker culture are finding their way into education, the workplace, online commerce, and especially manufacturing. This past spring, The Economist featured a Special Report on “A Third Industrial Revolution,” comparing this change to the shift from cottage industry to assembly line production. Hands-on creation, the sharing of results and process, post-consumer customization, and the ability easily to manufacture just one of something are all disruptive ideas that are having a tremendous impact on our communities.

As hands-on and collaborative companies like Etsy and Quirky transform neighborhoods in Brooklyn into “massive enclaves of Makers,” librarians like Reyes-Gavilan will be all in favor. “It would be irresponsible for Brooklyn Public Library not to devise a strategy to help this creative economy flourish,” he says.

Public libraries have already started supporting this need by adding media labs and creative learning commons. Over the past two years, they’ve included in the mix library-based Maker Spaces. Why not an Espresso Book Machine and micropublishing department in Brooklyn, or Boston, or, as costs come down, anywhere?

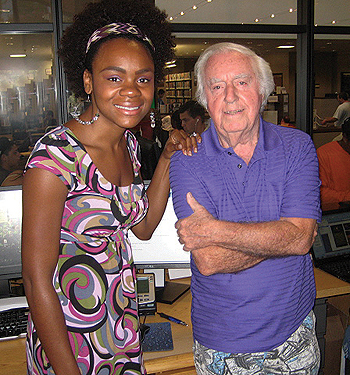

I Street Press is for everyone that is looking for a

Unique and informative presentation on formatting,

And having your book published. I highly

Recommend attending at least one or more

As the information you absorb, no doubt will Nourish

Your Enthusiasm and Determination, whether your a

Seasoned author or a novice, as watching a book or

Your book being printed before you is a experience to be

Remembered and appreciated

Thank You Alfred Guajardo

Just an update — since the writing of this article, both Darrien and Brooklyn have ended their partnerships and no longer have the machines.

Another update, since I’m revisiting this topic:

TR is correct – Darien and Brooklyn have both ended their partnerships. In addition, I believe that RCLS also no longer offers their services via Flash! Books – the information about it is gone from their website.

However, iStreet Press is still going strong at Sacramento, and several other public libraries have acquired EBMs and have some kind of self-publishing support programs in place. See a list of current locations at http://www.ondemandbooks.com/ebm_locations_list.php, then click through to see what that library is offering.