Launched yesterday, the Digital Public Library of America’s portal offers browsing and search access to a still growing aggregation of cultural heritage records from dozens of US cultural heritage institutions. At the same time, DPLA began offering programmatic access to its metadata stores, urging developers to create their own interfaces and access points to the collections. First impressions have been almost uniformly positive, though many have suggested avenues for further enhancements and refinements.

Launched yesterday, the Digital Public Library of America’s portal offers browsing and search access to a still growing aggregation of cultural heritage records from dozens of US cultural heritage institutions. At the same time, DPLA began offering programmatic access to its metadata stores, urging developers to create their own interfaces and access points to the collections. First impressions have been almost uniformly positive, though many have suggested avenues for further enhancements and refinements.

The new homepage features plenty of search options designed to lead to hours of exploration, as well as seven exhibitions that offer an excellent showcase of this budding project’s potential. Visitors can explore curated collections of authoritatively annotated photographs on subjects ranging from the history of activism in the United States to the history of sports stadiums in Boston.

Reactions on twitter were enthusiastic on Thursday. Rachel Frick, director of the Digital Library Federation Program, Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) posted “#dpla experiencing half million views per hour. NICE.” Jonathan Zittrain, Co-Founder and Director for Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society tweeted that “The @dpla has geocoded its archives — http://dp.la/map is wonderfully addictive. (Zooming in shows more and more.)” And the official account of NYPL Labs tweeted “And for nerds like us, not only does @DPLA offer a SICK API, but there’s a BULK DATA DOWNLOAD too!”

In an e-mail to LJ, Jason Griffey, Associate Professor and Head of Library IT for the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga also expressed excitement regarding the API, noting that he had been “obsessively reading and trying to understand the API framework and abilities.”

“Having watched the development of the DPLA for the last 2 years, and been lucky enough to participate in a couple of their development events, I think the launch is a huge success,” he wrote. “It’s not everything that everyone wants, but nothing is. I’m most excited about the public API, and the degree to which the DPLA is a platform, and not a destination. In my mind, the most important part of the DPLA is the platform, and the things that libraries can now build on it…. I’m very much looking forward to seeing what the librarians of the world can do with this data.”

Having programmers and other libraries build on their platform is one of the key goals of DPLA. In a recent LJ article covering the project’s scope and the goals, John Palfrey, president of DPLA’s board of directors and chair of its steering committee explained that “people worldwide will be able to come to dp.la directly to access materials from this online platform. But we expect that, far more often, people will access DPLA-related materials through their local cultural heritage institution—through a local public library, for instance, or through a historical society, archive, museum, or college library.”

Programmers have already begun releasing apps and programs that utilize the API. Two new apps were available to dp.la visitors: an app by programmer Jesus Dominguez that allows users to search DPLA and Europeana simultaneously, and the Library Observatory app created by Harvard’s metaLAB, “an interactive tool for searching and visualizing the DPLA collections, accompanied by an interactive documentary that weaves together history, visualizations, and audio about the making, use, and enduring significance of library data and the collections they describe.” And, Harvard’s Library Innovation Lab has launched StackLife DPLA, a site that allows users to browse scrollable virtual shelves that cluster books from the collections of DPLA, the Biodiversity Heritage Library, HathiTrust, and the Internet Archive’s Open Library based on multiple subject areas.

Initial Challenges

As a beta launch, the portal does have its flaws. Librarian, author, and founder of librarian.net Jessamyn West also described the site as “lovely. It’s basically a discovery layer to collections which, we presume, have less-good discovery layers.”

But she added that, at this stage, the project seems geared toward librarians, rather than the public.

“Please do not get me wrong, this is a huge enterprise and has the potential to be something really special. But my feeling is that, in reading through the website, that the dp.la’s ‘community’ is other libraries, they are a library for libraries. They are not, exactly, a library that is answerable to the public per se.”

West elaborated, explaining that there is “nothing wrong with that, but it’s actually a different model than what we think of as a library, one with programs and reference and people who can help you use it…. Until the point where we can actually make websites self-serve for people, I still feel like anything called a library needs to come with people.”

General searches do turn up plenty of interesting artifacts for librarians to pore through, such as historic maps, receipts, photographs, and census records, but what will the public make of such results?

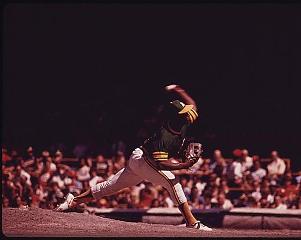

As a platform that is facilitating discovery of digital objects stored by other institutions, DPLA is also dependent on legacy metadata that can have its share of oddities or inaccuracies. LJ infoDOCKET editor Gary Price went digging, and quickly found some problematic examples on Thursday afternoon. For example, a search for Chicago’s Wrigley Field turns up a handful of images, three of which were created by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in July of 1973 and are stored by the National Archives and Records Administration. Two of the images purport to be from a game played at Wrigley by the Cubs versus the Oakland Athletics.

As a photo sourced from a large EPA collection, it is understandable that the general subject tags “Environmental protection,” “Natural resources,” and “Pollution,” are applied to a historic photo of an unnamed pitcher throwing from the mound during an early 1970s Major League Baseball game, but these are the only subjects associated with the photo, and none are relevant. There seem to be other problems as well. Notably, the date associated with the photo does not appear to have any relation to the content of the image.

“As far as I know, and I went back to a list of every box score … they would never have played each other in July of 1973,” Price said. “[Regular season] interleague play didn’t begin until [1997]. The underlying metadata in this situation is not DPLA’s fault. It’s the EPA’s or the National Archive’s fault. Whoever cataloged this record.” Still, small metadata flaws can be magnified when presented through the lens of an aggregation portal.

Price praised the DPLA interface, describing it as “very pleasing to the eye,” but noted that as a beta launch, it should probably describe itself as such to temper expectations during these initial phases. The launch has been highly publicized by consumer media outlets including National Public Radio and The Atlantic. Drawn by this coverage, the visiting public shouldn’t view this as a completed product, he argued. By the same token, the site could do more to highlight the additional capabilities of its partner institutions, and indicate how those partners will be helping DPLA grow, he added.

Practical Applications

But in general, the library community seems excited to see this project finally go public after years of work.

“I love the concept and how there are APIs for other institutions to develop their own apps using DPLA’s content. So great!” said Jen Cwiok, digital projects manager for the American Museum of Natural History. I think that the site is well organized and well designed. I immediately wanted to dive in and play around with it. The map and the timeline are innovative methods for retrieving and displaying data. The browsable subjects were also helpful in determining what content is like.”

After pointing out concerns about long-term funding for the project, Sarah Nagle, collections librarian for Carver County Library in Chaska, MN, noted that the DPLA site could be a big help for students working on multimedia assignments, although they will possibly need help to understand some of the search results and content.

“And, I have noticed during the last few years that ‘history’ and ‘heritage’ – anything connected, like historical fiction or reading about the Constitution or local history or keeping handcrafts alive – is a very important thing to a lot of people,” she told LJ. “Look at the explosion in genealogy resources and seekers.”

Others agreed.

“The potential for this platform to offer alternate histories/stories about Americans is so exciting!” Jessica Speer, Research Specialist, DePaul University, told LJ. “I’ve sent this around to my colleagues in the Social Science Research Center to see if they have ideas about how the DPLA might be useful in supporting research (or teaching) in the social sciences at DePaul.”

And like many librarians, Dalia Levine, Enterprise Information Architect for the Ford Foundation, noted that some features help foster exploration.

“Everyone wants a timeline but what is a timeline showing? A way to go through the collections? To follow your curiosity? I think how [they] did it is really interesting,”

Levine was also impressed with the volume of maps that include location data, and appreciated the site’s “clean” look.

“That’s where I think … conversations behind it need to stay focused,” Levine wrote. “Functional and clean is better than being the prettiest thing out there now. Worry about access to the info and keeping it growing and searching it rather than the pretty website. I think that will keep it more sustainable and relevant.”

Major congratulations to the DPLA on the launch and all the good content on the dp.la site! Kudos to its talented people for the hard work they’ve put in.

At the same time, the dp.la site is a good example of the need to work toward two separate but intertwined national digital library systems — one public, one academic. While I realize that dp.la is beta, I’m disappointed that the site wasn’t designed more with usability in mind for the typical American library patron, even at this point. There are serious content gaps, too — for example, too few links to items by and about greats like Mark Twain. Perhaps I’m expecting too much, but I want to see those as well as the wonderful special-collections content that the DPLA has packaged. Specifics are at http://librarycity.org/?p=7389. Tom Peters, the veteran academic librarian who cofounded LibraryCity with me, offers similar sentiments in comments under the post.

The good news is that the DPLA is still evolving and can still plan for the public/academic fork that LibraryCity proposes. Dan Cohen, current DPLA executive director, was a brilliant choice and would be equally well suited as director of the Digital Academic Library of America. A two-system approach would be more responsive to national needs, including those associated with the still-very-much-present digital divide.

Related: How the DPLA can honor the Five Laws of Library Science — and help libraries in Orange County, Florida — http://librarycity.org/?p=7136

David Rothman

LibraryCity.org

703-370-6540