Ebooks—it’s been a tough time. The bestselling fiction titles that users want are simply unavailable to libraries under terms that are friendly to our institutions. We’re left with business models in which publishers restrict the number of loans, expensive schemes that jack up the cost of those titles, or deals that tether us to specific reading devices.

Illustration by Mark Tuchman

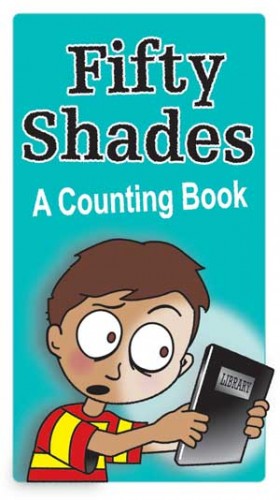

One option, championed by Jamie LaRue, director of Douglas County (CO) Libraries(DCL), is to pursue other sources of content. LaRue has struck deals with independent—meaning self-published—authors. DCL recently launched a deal to purchase titles from Smashwords, an aggregator and reseller of self-published content and so-called independent publishers, some of which offer hundreds of books on the site, while others publish just a couple titles. But the real problem is that most of the larger publishers and best-selling books on Smashwords deal in adult fiction—which is to say, erotica.

Even more troubling, in a recent interview by Publishers’ Weekly, LaRue was asked about DCL’s acquisition of children’s ebooks from Smashwords that were being made available with no review. “‘Can we vet every children’s book before we add it? I am not sure that we can,” LaRue responded, noting that he suspects DCL might “get stung once or twice.” This laissez faire approach simply will not cut it in school libraries. Truly inappropriate books in schools result in lawsuits, not minor stings.

I understand LaRue’s frustration and his desire to work actively toward a solution. Yet the maxim of quality over quantity certainly applies here. Publishers serve a critical role in the information ecosystem and are especially important for school libraries.

Unlike public and academic libraries, which have whole departments dedicated to new title acquisition, school librarians largely work alone. Even if we don’t always realize it, we rely on publishers to help with book selection. It’s the publishers who bear the cost of paying people to read the thousands of manuscripts submitted each year. Publishers pay for someone to then work with the selected authors to ensure that the books are accurate, grammatical, and appropriate in content and reading level for the intended audience. We’re left with the relatively easy task of having to select from the small percentage of books that make it through the established publishing houses each year. Our biggest challenge is that there always seem to be more books that we want than we can afford.

Imagine for a second if, instead of just having to consider among a few thousand vetted and professionally produced books, you had to wade through exponentially more choices? There are about 20,000 children’s and young adult books listed on Smashwords, but are any of them worth your time? The highest reviewed children’s book, Storm and the Magic Saddle, has 12 5-star reviews. But on deeper examination, I found only 10 actual reviews (two are duplicates), and only one of those reviewers has assessed any other books. There are also two reviews with no rating that question the accuracy of the information about horsemanship in the book as well as the age-appropriateness of the writing.

It all seems so, well, unprofessional. Given the publishers, aggregators, and professional review sources like SLJ that we’ve come to rely on, I just can’t believe that self-publishing is ever going to be the next big thing for libraries. Not when there are so many other great books still waiting to be read from the expert and established publishers with whom we already work.

Hi Christopher, Mark from Smashwords here.

Self-published (aka indie) ebooks may not be a solution for K-12 today, but they will be in the future if K-12 libraries make the right decisions today.

Correction: The majority of Smashwords books are *not* erotica. About 25% of Smashwords titles are erotica, so about 75% is not erotica. Our authors have released over 220,000 titles, so the erotica subset is around 60,000. Erotica is popular with readers, and much of the demand is now being met by indie authors.

When libraries acquire our books, they have the ability to filter out content by category, so if they don’t want erotic content, we won’t deliver it. Most libraries are filtering out our erotic content.

New models for acquisition and curation are necessary, and I’m pleased that we, DCL, Califa and others are helping to explore these models. To date, we’ve used our knowledge of aggregated retail sales as a proxy for title popularity, and to help libraries assemble their catalogs. As a distributor serving multiple major retailers, we have great data on what readers want to read.

In the future, I expect there will be more collaborative initiatives among libraries to read, review and recommend the best that indie ebooks have to offer. Indie ebooks are also finding their way into the mainstream book review publications.

As you evaluate the self-publishing space, it’s helpful to understand where the market is today, where it was five years ago, and where it’s headed in the next few years. Five years ago, self-publishing was seen as the option of last resort for failed writers who couldn’t get a publishing deal. In a sense, these writers were failed authors, because without brick and mortar distribution for what was then a print-centric world, most authors couldn’t reach readers even if they self-published in print.

Today, ebook self-publishing is becoming the option of first choice for an increasing percentage of authors. The stigmas of self publishing is disappearing.

With the rise of ebooks, and democratized access to major ebook retail distribution (something we helped open to indie authors in 2009 when we signed distribution deals with Barnes & Noble, Sony and Kobo), any writer in the world now has the opportunity to publish and get read.

At the same time publishers are denying libraries fair and reasonable access to ebooks, many indie ebook authors are starting to turn their backs on publishers. Indie authors are publishing direct to their readers via distributors such as Smashwords, and via all the major retailers, and many are not bothering to shop their titles to agents and publishers.

Further harming publisher relationships with authors, authors are miffed that publishers aren’t more pro-library. I moderated a panel last week at the RT Booklovers convention (romance writers conference), and Sylvia Day was one of my panelists. Her Crossfire series has over 7 million copies in print worldwide. She told the audience she’s not pleased that her publisher is denying her ebooks to libraries. I expect many authors will consider this anti-library sentiment of publishers when they perform their next cost/benefit calculus to decide if their next book will be self-published.

Authors want distribution everywhere, including to libraries, and if publishers won’t offer it, Smashwords will, working in partnership with library ebook aggregators such as Baker and Taylor, 3M and Overdrive, and via our own direct-acquisition service (used by DCL, Califa) called Library Direct (click my website link above to see our announcement of Library Direct).

In the next few years as ebooks continue to account for a greater percentage of the overall book market, publishers will have an increasingly difficult time holding on to their authors because authors are asking, “what can a publisher do for my ebook that I can’t already do myself, and that I can do better/faster/more profitably?”

This means that in the future, even if publishers do come around to embrace libraries, they still won’t have all the books you want.

Over the last five years, the practice of indie ebook publishing has become more professional. Indie authors are quickly innovating the best publishing practices of tomorrow, and in the process they’re hitting all the bestseller lists. As I write this, for example, two Smashwords titles are among the top-10 bestsellers today at the Apple iBookstore. Nearly every week now, you’ll see indie ebook authors in the New York Times bestseller list (and many of those books are carried by Smashwords). This was rare a year ago. A year from now, it’ll be more common. Within three years, I believe over 50% of bestselling ebook titles will be self-published, and I’m probably being too conservative.

Many bestselling indies, borrowing a page from the playbook of publishers, are outsourcing their editing and cover design to professional freelancers. Indies are investing in their books. The professional care that went into producing traditionally published books is now finding its way to self published books. In the years ahead, these indie authors will become smarter and more professional, because the secret to reaching readers is to publish professionally. In other words, you’ll see more better books coming from this space in the future. Libraries can help.

Self-published ebooks might today account for 25% of ebook sales, according to one industry watcher – http://davidgaughran.wordpress.com/2013/04/12/self-publishing-grabs-huge-market-share-from-traditional-publishers/ Regardless of the percentage today, it’s clear this percentage is on the rise, and one need look no further than the bestseller lists. These are books readers want to read.

Self-published ebooks, and ebooks from indie presses, are the future of publishing. One need look no further than the trends regarding ebooks as a percentage of the book market, or the increasing percentage of bestsellers published by indies, or the growing frustration authors feel with publishers.

It’s time for libraries to hitch their wagons to this horse and support the development of this market with their dollars and expertise. If libraries delay stocking these books, libraries will undermine their own public charter of making a diverse range of quality books accessible to local patrons.

Libraries have an opportunity to enable a brighter bookish future for libraries, patrons and authors alike by supporting the best indie authors with their acquisition dollars, and by launching community publishing initiatives to help local writers to write and publish professional-quality books. I outlined some of the opportunities the other week over at The Huffington Post: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/mark-coker/library-ebooks_b_2951953.html and I talked about an innovate pilot program we launched in cooperation with Henry Bankhead of Los Gatos Public Library.

At a time when publishers aren’t being friendly to libraries, libraries have an opportunity to support the next generation of publishers (self-published authors!) and thereby ensure a stronger supply of books for patrons.

In our research, we found our 60,000+ indie authors are overwhelmingly pro-library, unlike traditional publishers. Indies want their books in libraries, because they recognize that libraries are tremendous engines for discovery, for readership, and for driving retail sales.

If indies are ready to support libraries, are libraries ready to support them in return?

I urge libraries to roll up their sleeves, experiment, and share what they learn as Jamie is sharing. There will surely be potholes and stumbles along the way, but I have no doubt history will be on the side of indies.

Thanks for the opportunity to provide feedback.

Mark, thanks for responding. I certainly agree with most of your points…but let me explain a bit further the perspective I am coming from.

Despite your clarification that only about 25% of Smashwords titles are erotica, I will have to stand by my specific statement that many of the top publisher and top title lists seem to have a higher proportion of erotica. Looking at the list for the 100 most downloaded books, 5 of the top 10 books are erotica; 9 of the top 25 best sellers are either tagged as erotica or have a 17+ rating for high levels of sex.

But my point here is that as much as I think Jamie is doing some great work to explore the indie-author concept, I just don’t see it working for schools. Or at least not through Smashwords as it currently exists. I am writing from the perspective of not just a librarian who has learned a great deal about publishing and ebooks, but also as a school administrator. In most states, school administrators are charged to act “in loco parentis” for their students. That high level of care, as if they were the students’ parent, requires that we take proactive steps to ensure safety.

If a school were to sign a deal with Smashwords and a parent visited to site to discover even 25% of the titles being sold are erotica the school would be facing a real issue. It isn’t anything personal from me, it is just the fact that schools and school libraries are held to a much stricter standard for content filtering. From an information freedom perspective, it is fine that Smashwords still sells incest-based erotica, but from a school purchasing perspective that is just begging for really bad press and some quite attention grabbing headlines.

Schools cannot afford to get stung even once.

What you are doing is laudable, but it just isn’t right for schools at this time. Perhaps what is needed is another service for just children’s and YA titles that has the level of oversight and review that school libraries have to have?

The real problem is that Smashwords doesn’t perform the functions that a true children’s book distributor like Follett, Mackin or Perma-Bound does–it doesn’t have a collections department that reviews titles, categorizes them and weeds out inappropriate titles before they ever get to customers. Smashwords simply passes through whatever it gets from authors, and depends on customers to identify inaccurate or inappropriate titles.

The problem doesn’t lie with self-published children’s books per se–rather, it lies with vendors that are unwilling to assume the cost of and responsibility for reviewing titles. A self-publisher whose title(s) are vetted by a qualified distributor should be equivalent to those published by independent children’s publishers.

Hi Len, the titles we distribute to libraries are in our Premium Catalog. They have all been vetted by live humans to meet or exceed the requirements of the retailers to which we distribute. Every book is opened and inspected. While the vetting isn’t to the level provided by a publisher (we’re not vetting for quality or marketability, for example), we don’t pass along everything.

Hi Mark,

Thanks for your clarification! I didn’t know that you have a separate catalog of reviewed titles.

Hi Mark,

Just wondering if you could elaborate on the vetting of titles for the Premium Catalog. What are you vetting for, if not quality? Thanks for any additional information you can provide.

Chris, I’m willing to admit that there are differences between the needs of school and public libraries. But as Mark pointed out, I think we have to be careful to reject a whole STREAM of content out of hand. For instance, is it still unprofessional to accept self-published works by well-established authors with whom your library has a long relationship? Or is the issue just buying in bulk (which we did to build a large sample collection — and even that, as Mark illustrates, wasn’t just blind) versus buying one by one?

I understand and respect that schools may have had far closer and more productive relationships with their publishers than public libraries have had with the Big Six. Good for you. But I continue to believe that all kinds of libraries have to keep an eye on emerging trends and best practices. As you know, things are changing rapidly. It’s not just what publishers and libraries prefer — it’s what AUTHORS do.

Jamie, as I noted above, the whole point of this is to focus on the specific differences between school and public libraries. Would I accept self-published works from an established author? Probably, but you better believe I would want to make sure someone from a school had read them and passed them as okay.

That is one of the key services that school libraries get from children’s and YA publishers. The editors from established houses push boundaries (see banned lists here) but a school can also defend the selection of a book from a publisher has having been reviewed and approved by a knowledgeable expert.

Remember as well that most school libraries are staffed by, at most(!), one person. Education cuts across the country have all but eliminated support staff from many libraries and have led to a single library covering two, three…sometimes FIVE libraries. Outside of the largest districts, there is no acquisitions department to review books and ponder each selection.

Self-published titles can be excellent, but things are just too wide open and unknown for them to be a regular part of a school library’s collection without an additional support structure to identify the best (and most appropriate) titles.

Storm and the Magic Saddle is still the most highly rated children’s book on Smashwords. But if you really read the reviews at http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/122526 things get really odd really fast. Not a great advertisement for the site having that at as the highest rated book. The top rated YA books look much better, but also have more potential for issues and need closer review.

So really it is about the differences between school and public. Self-published can be a content stream right now for public libraries, but much more work is needed for schools.

So it we admit that the self-published eBook content stream may not be optimized now for public school libraries (more about private school libraries in a bit), and this being because reviews for this content are not prevalent nor is there a system for their consistent production, the question remains “what are we going to do about it?”. Also I want to point out that the main factors that make self-published eBooks attractive, not really mentioned above are PRICE and FLEXIBILITY.

We like self-published and indie works because of the low prices. Similar to our library’s use of the open source ILS Koha – self-published books allow us to stretch our budget. A big six title might cost us $50 to $80. Self-published/indie … more like $2 to $10. Also flexibility: We define what our open source ILS will do and we take responsibility for making it so. Free self-publishing platforms allow anyone to define a book. Not “just anyone” but more like “all inclusive everyone”. They will also allow any library, school or other entity not just to acquire content, but create content. Thus a private school library could in theory publish its own textbooks (not needing to go through the oversight of a school board) or perhaps scan, OCR and upload yearbooks. However the larger point is that Koha in Maori means “a gift with obligations”, such that the low price of self-published eBooks comes with the condition that they do not have a massive publishing vendor edifice behind them and it requires more work to separate the wheat from the chaff. Thus Library Direct, thus the need for wide outreach to librarians, readers, teachers and administrators to get involved and review self-published eBooks as a service to the profession. This will help define what we need and what we are looking for as well as assessing what is already there. Perhaps we need to re-examine our reactive stance and expectation for vendors to do this for us and get more proactive? Perhaps major readers’ advisory/reviewing tools (like Novelist and NetGalley) could get involved to integrate self-published e-only eBook content?

In addition to all that, creative writing students and teachers might think about self-publishing platforms as a tool for creating and publishing student work. What better way to educate youth and support their voices and talent?

Surely you didn’t think that I would talk about a problem without a solution or two up my sleeve? Stay tuned just a bit longer as I work some things out…..

I recall visiting New York Public Library in 1963, when every book that entered the cataloguing section was read – and now a school district can’t afford to check whether or not an e-book is really suitable for its kids. It’s the end of civilization as we know it, folks :-)

This is a compelling article and an even more compelling set of comments that have followed. As a parent of a school aged child with reading challenges, I’m intrigued by the intersections of these topics: e-books, the world of self-publishing, and how to “get it right” in terms of standards for e-books that end up offered in school libraries. It does strike me that subscription-based e-book apps for children like Bookboard.com that have a children’s librarian curating the collection of titles they offer addresses some of these issues quality control for children’s e-books. I’m a parent using this service and don’t worry about the content at all in this regard. See this article in Forbes on their approach: http://www.forbes.com/sites/jordanshapiro/2013/04/17/bookboard-streams-kids-books-to-the-ipad-but-are-e-books-good-for-your-children/

Here’s a perspective from a published (by brick and mortar publishers) author for children and YAs AND a school librarian. I would never even add something to my library that *I* had self-published! I’m a pretty good writer, if I say so myself. But, as I tell students when I talk about writing, I come at a book after months of research. I sometimes forget what my readers should already know, what they probably don’t know. I get so wrapped up in what I’m writing, it makes sense to ME because I’ve been living and breathing it; it’s easy to overlook flaws in flow when you’re that absorbed in a subject. And so, I tell my students, that’s where my editor steps in. It’s my job to write; it’s the editor’s job to make sure my writing is the best it can be, that it will make sense to a non-expert reader. I love showing kids a ms. that an editor has marked–often on every line. I also explain to my students the difference between many pages or sites on the Internet (unedited, un-fact-checked) and databases (selected from published–and therefore edited–work, chosen for quality), how and why one just might be more or less reliable than the other. Yes, traditionally published books have a (higher every year) price. As both an author and a librarian, it’s a price worth paying for quality.

You seem to assume that no self-published book goes through a review process. This is true of some self-published books. Then you have the books like mine, The Oz Saga series, which went through both a copy-edit and a full edit. Not to mention the proof-readers. I actually passed up on several agents who thought it was a great and saleable book. I did it for one reason: I want control over my material. Being a seasoned graphics designer, I wanted the full say in how the book was laid-out and the cover design. The big issue with going a traditional route is that authors receive very little money for their work (sometimes pennies per copy), and STILL have to do most of their own marketing. This on top of the fact that it can often take more than 5 years from a finished manuscript to a printed book. All of this why I choose to self-publish my middle grade book series. It has nothing to do with quality, and all to do with control.