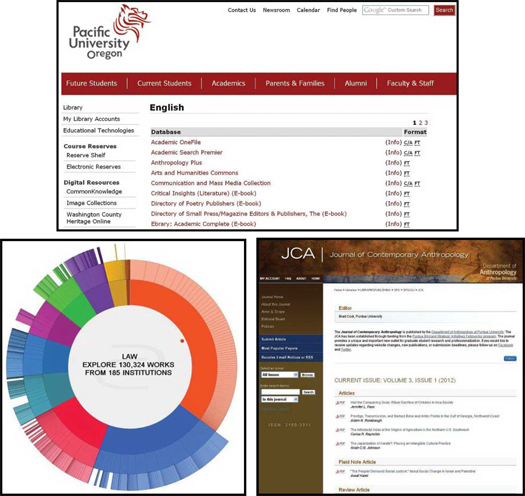

- SOMETHING IN COMMON Pacific University (top) includes links to the Digital Commons Network alongside commercial databases.

A Digital Commons journal (below) from Purdue University

Visitors to the new Digital Commons Network (DCN) portal recently launched by bepress are greeted with a clean layout featuring one prominent, ornate graphic—a large, three-layered, color-coded wheel encircling a simple invitation: “Explore 691,431 works from 275 institutions.”

As the new portal to content produced and stored using bepress’s widely used Digital Commons publishing and institutional repository platform, those numbers will continue to grow, but two key qualities of this resource are expected to remain constant. These works will all be full text, and they will all be open access.

“From the reader’s perspective, we wanted no dead ends,” explains bepress president and CEO Jean-Gabriel Bankier. “We wanted their experience to be that when they browse, they would always find a PDF. So if you’re in the network, you will never find only metadata. And you’ll also never find any restricted content. So every reader experience will end at a PDF. And when they’re in the PDF, they can click a link to take them back to the network. The whole thing is integrated.”

Founded in 1999 by University of California, Berkeley professors Robert Cooter, Aaron Edlin, and Ben Hermalin, bepress began as a suite of online editorial management tools for producing peer-reviewed journals. In addition to the Digital Commons, the for-profit company has also produced the research announcement tool SelectedWorks.

Given libraries’ institutional mission to provide broad access to works across a wide variety of disciplines, an online portal promising perpetual, free access to hundreds of thousands of full-text, peer-reviewed articles, Ph.D. dissertations, master’s theses, conference proceedings, research data, and other content sounds like a logical next step in terms of cross-institutional collaboration. Indeed, bepress views DCN as a natural extension of the mission behind its Digital Commons software service, which enables institutions to publish their own professional quality, peer-reviewed journals, create landing pages for their faculty to highlight research published elsewhere, and build institutional repositories in a way that consolidates a university’s intellectual output. In each case, the primary goal of the Digital Commons platform is raising the visibility of an institution and its research. DCN helps achieve that goal by making it easy for users to search all Digital Commons repositories at once.

And while institutional repositories are typically indexed by search engines, the portal makes it very easy to access a large collection of open access (OA) materials that are specific to a discipline, notes David Scherer, scholarly repository specialist for the Purdue University e-Pubs Repository, IN.

“With a lot of open access materials, depending where you place them—whether it’s a public website or a private faculty web page—they can be hard to find,” he says. “If I’m trying to find items on civil engineering, am I going to know to look [in the repositories] of institutions x, y, and z? This is a database that I can use as a resource, just like any other library-based resource or tool, to find these kinds of materials.”

Color wheel

The starburst wheel graphic on the portal’s network.bepress.com homepage helps illustrate this concept to newcomers. The wheel features ten color-coded disciplines: law, social and behavioral sciences, arts and humanities, life sciences, physical sciences and mathematics, education, engineering, medicine and health sciences, business, and architecture. The size of each color-coded area reflects the size of each discipline’s collection relative to the rest of DCN.

Two additional layers radiate out from this central “discipline wheel.” The first narrows down the discipline into a selection of subdisciplines, while the second allows users to pick from subjects within that subdiscipline. For example, hover a mouse pointer over the innermost, purple segment of the discipline wheel, and a visitor is encouraged to “Explore Medicine and Health Sciences.” Move the mouse to the second purple layer and the wheel will advise users to “Explore Medical Specialties” or “Explore Public Health.” Or users can mouse out one additional layer beyond the “Medical Specialties” subdiscipline to browse a selection of subjects including neurology, pediatrics, or radiology.

At any point, users can click on any segment of any layer of the wheel, and the wheel will begin a brief animation, with the selected discipline, subdiscipline, or subject swallowing up the rest of the wheel and navigating users to their chosen commons area where they can then proceed to a list of full-text PDFs.

To be clear, typing a couple of keywords into the “Search Entire Network” box, also located on the homepage, might be a more efficient method than mousing around on this graphical browsing element. But from a design perspective, this colorful wheel plays an important role in communicating the vision and purpose of DCN and the institutional repositories served by Digital Commons.

“We wanted for each repository to be able to show visitors who came there, visually, what’s in it,” Bankier says. “It’s a way for them to describe, graphically, what are their areas of strength? What are their areas of expertise? Each of the repositories in Digital Commons has its own graph, its own discipline wheel.”

For individual faculty members and researchers, DCN also helps illustrate that a contribution to an institutional repository is a contribution to its discipline, Bankier adds.

“One of our goals, from the perspective of the authors, was to address the ‘island problem,’ ” he says. “They saw their own institutional repository as an island, and they didn’t see how it connected with their discipline. And authors care first about themselves, then they care about their discipline, and only then care about their institution. We wanted [to illustrate] that a contribution to their repository was a meaningful contribution to their discipline as well.”

Isaac Gilman, an assistant professor and scholarly communications and research services librarian for Pacific University, OR, agrees with Bankier’s assessment.

“Having all of the repository content from a variety of institutions accessible through one portal and one place makes it a lot easier to have the conversation with students and faculty about how, when they’re contributing to our institutional repository, they’re contributing their work to a broader disciplinary conversation,” Gilman says. “Within the [DCN] portal or platform, they can see their work right next to work from people within their discipline…. That’s really valuable in helping to emphasize that what you put in our repository doesn’t just stay at Pacific and isn’t just going to be related to other work at Pacific, but it’s going to be related to other work across the country and across the world.”

Friendly competition

Each commons area page also features lots of top-level, at-a-glance statistics, including the number of articles, authors, and downloads, and a short list of institutions and authors who have contributed the most downloaded papers. Users can also click on a link to a pie chart that illustrates which institutions have contributed the most content to a specific commons.

One librarian has already found this pie chart to be a great motivational tool. In theory, most faculty will quickly understand the benefits of a repository and the ways it can help them raise the profile of their work and their institution. But encouraging faculty to contribute articles and data regularly can still pose a challenge. Figuring out which of their articles can be legally contributed to an OA repository and then uploading their work take time. If there’s no momentum behind the repository concept in their department or in their field, contributing can get pushed far down an individual researcher’s list of priorities.

So, at Iowa State University, digital repository coordinator Harrison Inefuku used DCN’s institution pie chart to stoke a spirit of competition. Iowa State launched its Digital Commons repository in April 2012, and when Inefuku began efforts to engage faculty, the university’s agricultural and biosystems engineering department was the first to buy in to the concept as a group.

“After bepress launched the Digital Commons Network, I was looking at it, trying to see if it could help me try to reach these faculty and try to get them to participate,” Inefuku says. Opening the institution pie chart in the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons area, he discovered that Iowa State had already become the second-largest contributor in this subject. It illustrated how much the repository had already grown, while giving the agriculture and biosystems engineering department faculty another goal to shoot for—the number of repository items contributed by their peers at the University of Nebraska.

“[Nebraska] has had its repository for a long time…the number of items in every subject are a lot higher than ours just starting out,” Inefuku said. “I thought it would be a great opportunity to show them ‘this is where we are, this is where Nebraska is, and I would really like us to pass Nebraska.’ ”

It worked. He presented his challenge to the department in December 2012, and by March 2013, Iowa State was responsible for over half of the content contributed to the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons.

Open for access

Aside from showcasing a university’s research capital or encouraging faculty to contribute to their institutional repository, DCN has its own merits as a full-text database that any library can encourage patrons to try.

Pacific University has already taken direct links to the different disciplinary commons areas and included them in the list of online databases to which the university offers access. A student searching biology-related databases, for example, will find a link to the Life Sciences Commons on the same page as resources from Gale, ProQuest, EBSCO, and Springer.

“I really do see it as a resource that is just as valuable as a [commercial] database aggregator’s product,” Gilman says. “And we want to try to make students aware of the wide variety of scholarly content that’s out there, because repositories do have a wide variety of really useful content, ranging from formal publications all the way to gray literature. And we’re encouraging students and faculty to recognize the value in this variety of scholarly products.”

“It drives users to our repositories,” says Purdue’s Scherer. “We’re always trying to increase the visibility of our open access repositories and our content, and we’re doing this in a mechanism that users are most familiar with—having a database. Compare it to how journals and the indexing databases work: you have a journal, and it has a web presence, but then, it’s enhanced tremendously by [inclusion in] a database.”

Inefuku agreed, noting that while the open access movement has created new opportunities in academic publishing, there have also been unfortunate side effects, including the rise of predatory journals. As a network of repositories that have been vetted by their respective institutions, DCN offers a reliable starting point for students and researchers seeking open access content.

“When it comes to searching for information online, especially [at] an academic institution, we still have to do our part with information literacy, telling our researchers and students how to find quality websites, how to find quality information,” Inefuku says. “With the open access movement, it’s creating a lot of opportunities to get scholarship out there. But…there’s a flip side to that as well.”

In its first year, DCN already appears to be having a significant impact on downloads from Digital Commons repositories. Six months after launching in November 2012, total full-text downloads from the approximately 300 repositories that Digital Commons serves had reached 130 million—up 85 percent from the same period a year earlier, according to Bankier. And well-used institutional repositories could give university administrators additional motivation to support open access, he says.

“Open access is kind of like preservation. It doesn’t have funding behind it,” Bankier says. “I would argue that this is a sustainable model, because the work that the library is doing directly connects to the mission and goals of the institution. Demonstrating value and strengthening reputation are things that all universities care about and are willing to fund…. This is a win, win, win. The university wins because it gets more visibility by sharing its research, the library wins because it gets to save [database subscription fees], and the public wins because they get free access to scholarship that they wouldn’t have had access to otherwise.”

Matt Enis (menis@mediasourceinc.com is Associate Editor, Technology, LJ

I like very much the last sentence: “I would argue that this is a sustainable model, because the work that the library is doing directly connects to the mission and goals of the institution. Demonstrating value and strengthening reputation are things that all universities care about and are willing to fund…. This is a win, win, win. The university wins because it gets more visibility by sharing its research, the library wins because it gets to save [database subscription fees], and the public wins because they get free access to scholarship that they wouldn’t have had access to otherwise.”

DCN may become a good alternative to Google Schoolar and Wikipedia. But it doesn´t appear in the results of search engines as Wikipedia.