Talk about a revolution. Since Amazon unveiled the first Kindle in 2007, digital devices have dramatically changed the way kids read and even think about books. But it’s less clear how ereaders and tablets will affect libraries and schools. As any librarian who’s dealt with ebook adoption can quickly tell you, “It’s complicated.”

While many schools and libraries have launched pilot programs to get ereaders and tablets into the hands of students or have allowed them to bring their own devices to class, it’s still early days. As such, there’s mostly just anecdotal evidence from educators about how well these devices work in school.

For sure, there’s plenty of hype to support device adoption: they’re easy to use. They’re easy to carry. They’re less intimidating than laptops or desktop computers (for both teachers and students), and they lend themselves to “play.” Best of all: kids love ’em.

Students at Seneca (IL) Grade School claim they can read faster on ereaders, according to Kathy Parker, the school’s librarian. Some kids also like being able to quantify the amount of text they’ve devoured, referring to the percentage they see on the bottom of the Kindle screen, informing them how much of a book they’ve completed. Overall, students are enthusiastic about ereaders and, by extension, reading, she says. (The same apparently goes for adults—a recent Harris Interactive survey found that ereader owners buy and read more books than consumers who don’t own ereaders.) Moreover, the latest electronic devices have particularly inspired reluctant readers, says Parker, who has penned a chapter on the topic for the upcoming book No Shelf Required 2, edited by Sue Polanka (ALA Editions, 2012).

Parker runs a fairly extensive Kindle program at Seneca, with some 200 ereaders distributed among various grade levels and reading groups. What features of the Kindle are her K–8 students crazy about? Start with the built-in dictionary and then add highlighting, variable font sizes, text-to-speech, and note-taking capabilities. There’s also a “popular highlights” feature, whereby readers can see the most frequently highlighted passages, and that’s been a great “conversation starter”—even among second graders, says Parker—to encourage literary criticism, of sorts.

Parker preloads the Kindles with more than 150 titles from her teachers’ recommended reading lists—everything from Suzanne Collins’s best-selling “Hunger Games” trilogy to classics like Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo. Teachers then check out the devices and pass them out to their students.

Even though she’s handling content on the devices for whole classes rather than individual library patrons, Parker says that managing the Kindle program has been a time-consuming process. Imagine registering, loading, tagging, tracking, and charging some 200 devices. “But it’s a good challenge!” she says. “The students are excited about using this new technology for reading.”

Roadblocks to purchasing

Indeed, there are lots of challenges when it comes to administering tablet and ereader programs, in no small part because these devices and the marketplaces that support them (whether Apple, Google, Amazon, or Barnes & Noble) are geared toward consumers, not schools and libraries. For example, Lisa Perez, a media specialist with the Chicago Public Schools (CPS), says that her district wasn’t able to embrace the popular Kindle devices because there weren’t any vendor agreements in place that would allow teachers to use purchase orders, a district requirement, to buy Amazon’s devices or digital content. And while CPS has purchased a few Nooks, Perez says she wasn’t sure the Barnes & Noble Managed Program, which is run through local stores, would scale well across a district the size of Chicago.

So, like many districts, CPS has begun to adopt iPads. More than 20 of its libraries have purchased at least one, and five district libraries have received 32 Apple tablets, a MacBook, and a syncing cart as part of a grant-funded “iPads in the Library” program. The participating librarians have been documenting their experiences and posting recommendations about the best practices on a wiki. The resources include rubrics for assessing ebooks and apps, sample student contracts, tips on how to physically tag iPads for syncing and circulation, and information about buying through Apple’s Volume Purchasing Program.

Even with all the excitement about iPads’ educational potential, there are still plenty of hurdles to making them work smoothly in libraries. “Apple doesn’t allow ebooks to be included in its Volume Purchasing Program,” Perez notes, “so we can’t leverage our collective purchasing power. In addition, we need a cloud-based solution, so we don’t have to sync certain books to specific iPads. The current process works for a classroom teacher who may want 32 identical iPads, but it isn’t efficient for a librarian who needs different devices. We would love to see the ability to buy [books via the iBookstore] at discounted prices and house them on iCloud in accounts associated with each school.”

The syncing of devices—getting the right content onto the right device (or devices) or associated with the right account (or accounts)—remains a labor-intensive venture, as Parker can tell you. It’s one of the striking reminders of how tablets and ereaders are designed for the individual consumer with one account. Despite the growing popularity of these devices in schools and libraries, some of the major hardware makers—Amazon and Apple, primarily—have been slow to accommodate the needs of those who are implementing these devices at a large (school or classroom) scale.

Getting devices, platforms to play nice

Another problem facing schools and libraries is interoperability: Do different devices work together, can content move from one type of device to another, and do these all integrate with a library’s information system? There’s been some improvement in making user information available and synced across devices, thanks to the cloud. Kindle’s “Buy once, read anywhere” slogan is a nod in that direction: you can read your Kindle ebooks on multiple devices, and thanks to Amazon’s Whispersync technology, books open to the last page you were on.

But the slogan’s a bit misleading, too, as there’s still the potential of finding oneself locked into a particular platform, device, or marketplace. Some apps are only available on Apple devices, for example. Apple iBooks can only be read on iPads, iPhones, and iPod Touches—but not on Macs. Kindle ereaders are tightly bound to the Amazon store, and Nooks to Barnes & Noble. For libraries with multiple types of devices—something that’s not that uncommon considering today’s choices in computing devices: iPads, iPod Touches, Nooks, Kindles, Windows desktops, MacBooks, or Chromebooks, and so on—it can be incredibly challenging, if not impossible, to maintain and transfer digital content across platforms and systems.

While digital content distributors, such as OverDrive, provide ebook checkout that supports multiple devices and file formats (including PDF, ePUB, and AZW files), the cost is prohibitive for many schools and libraries. And even if you can afford OverDrive, there’s no guarantee that the books students and teachers want are available electronically—or available for ebook loans. Indeed, although Amazon’s CEO, Jeff Bezos, talked about books’ “stubborn resistance” to digitization when he rolled out the Kindle four years ago, it’s the publishing industry—not books or their readers—that seems to be slow to move, particularly when it comes to making ebooks available to libraries.

The accessibility issue

But it isn’t just the “new rules” of publishers and digital content providers that are changing how these new reading devices are handled. For many schools, their newly purchased ereaders and tablets only circulate onsite, remaining in the library or in the classroom. In other words, students aren’t able to take the devices home. That’s hardly surprising, particularly when you’re talking about an expensive piece of equipment like an iPad. But this raises questions about other aspects of accessibility. What does it mean if students can’t take their digital library books or textbooks home? Is there still a way for them to access an ebook online or on a personal device? To address some of these questions, CPS has created a Virtual Library, which contains more than 7,000 books, available 24/7 at home and at school in formats that work across devices, including via a Web browser.

Another challenge? Integrating all these various subscription services and ebook portals into a single library catalog that’s easily searchable by students—a catalog that makes it clear where on the physical bookshelves or on mobile devices they’ll be able to locate a title. Norma Thiese, a media/technology consultant at the Keystone Area Education Agency in Iowa, says that discoverability remains one of the biggest challenges that librarians (and their patrons) face with ebooks. Library users need to be able to find the titles they’re looking for, receive alerts when there’s something new, and—of particular importance to school libraries—find content that matches their grade or reading level and that clearly indicates if the ebook has “read aloud” functionality.

It’s clear that the increasing adoption of mobile devices like ereaders and tablets by schools and libraries still faces a number of obstacles. How will libraries meet the growing interest in and demand for ebooks? How will circulation policies change, and how will library systems and processes adapt? And how will schools and libraries ensure that all students have access? But these are new devices, bringing with them new challenges. And even with all these hurdles, librarians are adamant: if tablets and ereaders are what students want—if these devices really do increase their enthusiasm for reading—then they’ll find ways to make the devices work, even if that involves, at least for now, a lot of work-arounds.

Sticking Points

These are the top five issues libraries face when it comes to using ereaders and tablets in school.

1) Platform lock-in and lack of interoperability

2) Administering devices

3) Availability of the titles students and teachers want

4) Integration of the ebook catalog with the library catalog

5) Cost of both devices and ebook

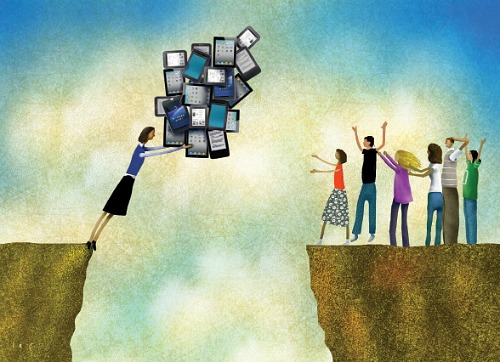

Illustration by Dave Cutler.

Another issue that often crops up is infrastructure-related. If a district plans to adopt tablets or e-readers on a large scale, they’ll need some way to connect those devices to the Internet. Often, though, schools won’t have adequate wireless density.

Sure, they may have *coverage*, so that every spot within the school gets a signal, but they probably won’t have *density* (meaning that the wireless network has too few access points and too little bandwidth to accommodate a substantial increase in the number of connected devices).

This is something one of our engineers is actually drafting a blog post about this morning. As soon as he posts it, you’ll be able to read it here: http://is.gd/q0OGL9

Adam, I am not sure this is really an issue with an e-Reader (Nook, Kindle). In reality, it only needs to be connected to the internet to download the book. Once downloaded, the device is not dependent on being connected to the internet.

However, on the broader picture of things like iPads or tablets replacing textbooks with interactive websites and other internet resources; then, yes, districts will need to upgrade their wifi technology.

Suzanne,

Yes, I suppose you are correct. I should have been more specific there. :-) Anyway, for those who are interested, the blog post by our engineer is here: http://is.gd/ezVnGN

– Adam

and these devices are valuable and fragile too:( where i live cell phones and ipods that belong to kids, even highschool age kids, get lost, broken and stolen. Tablets are not made sturdy enough for kid use, that was not the intended market.

Yes I had the same concerns with patrons at libraries checking out Libraries with the new Mediasurfer but then I heard that they came with a hard case. Also there is the new Pelican iPad case, which is pretty darn sturdy looking http://dondesestalabiblioteca.blogspot.com/2012/01/patron-proof-pelican-ipad-case.html

Certainly it would be cheaper for schools and information centers to invest in a strong case than to have to replace a tablet frequently.

These challenges aren’t new and aren’t unique to schools. We encounter them on a daily basis and it pains us to see organizations tripping over the exact same challenges. We’re creating a repository of best practices based on our engagements assisting complex organizations deploy enterprise mobility. The biggest culprit is not really thinking through the organizational goals for the devices. Folks are quick to buy first and figure it out later when what they really need is a methodical and detailed approach to deploying these devices in the first place. Our experience shows that it is best to let the overall outcome goals drive specific use cases as well as consider integration requirements (with existing systems), infrastructure requirements, policy (e.g., security and privacy) and application governance considerations drive the decision regarding devices and applications. We were in a meeting with a school this morning when a teacher whipped out an iPad and started sifting through the apps — which were not well organized or presented but not integrated with any back office or management system. It was clear that the system really wasn’t taking this deployment seriously in the sense of realizing the potential of what these devices can really do. We see a lot of leaders who in their well meaning but far too eager desire to deploy tablets as learning devices are rushing out and buying devices without a methodical and thoughtful approach to creating desired outcomes in a scalable and sustainable manner. It’s good for us though — we’re building quite a successful business helping large enterprises — including schools — get this right. The challenges are numerous but our experience shows that they are not insurmountable.

It’s not necessarily an “either/or” in our district. We are just kicking off the VITAL grant program this week, in which five of our high schools will receive sets of Nooks to use for ereader book clubs and other uses – as well as some iPads. Also, although iPads have ereader functionality, but they support a lot of other uses, such as research and digital content creation. As platforms and devices develop and mature, it is good to keep a watchful eye and see what works best for our students and teachers.