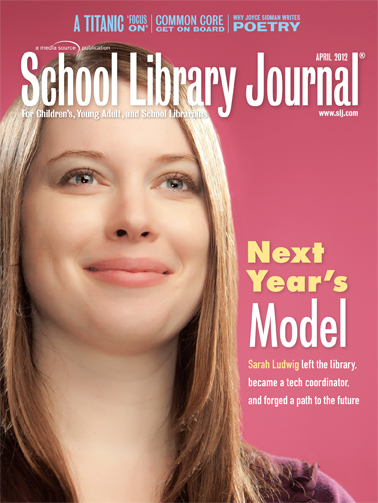

Sarah Ludwig left the library, became a tech coordinator, and forged a path to the future

By Linda W. Braun

I’ve known Sarah Ludwig since she was a library school student at Simmons College. When we first met, her goal was to be a teen librarian. Then one day Sarah told me about a school library job she was thinking of applying for. Sarah took that position, then moved into teen librarianship at a public library for two years, and now she’s back in a school. But her title isn’t librarian, it’s technology coordinator.

Over the past year, it’s become very clear to me that what Sarah’s doing at Hamden Hall School in Connecticut could be a new model of librarianship. While she isn’t called a librarian, a lot of the work that Sarah does with students and faculty is very similar to—or, in some cases, identical to—what school librarians do.

Is this the future of the profession?

LWB: What is your job?

SL: I’m the academic technology coordinator at Hamden Hall, an independent preK–12 day school. There are two major aspects to my job. One is related to the classroom: I develop and teach weekly technology classes to preK–6 classes, and I support technology projects—meaning I teach special classes—in grades 7–12. The other is working directly with faculty. I train teachers and identify technology that can be integrated into the curriculum, and then I work with faculty on the integration itself. My role in the lower school is changing a bit this year; I’ll be more of a co-teacher. It’s our goal for lower-school teachers to start developing technology projects more autonomously and even teaching some tech skills themselves. That model’s worked very well in the middle and upper schools.

What drew you to this job?

My first job out of Simmons was as a school librarian, but I decided after three years that I wanted to give public libraries a try; that had always been my professional goal. When I finally did work at a public library, I had a hard time making strong connections with the teens in the community—they were really busy with school, sports, and other after-school activities, so there were very few regulars. I ended up really missing the close bond with kids that I’d been able to make in a school, where you see your students every week or daily, and you can really watch them grow.

It took me a while to decide if I should apply for my current position, because it’s not a library job. I wondered if I was qualified. But I realized that the major parts of the job description were the elements of librarianship that I love—instruction, teaching students new skills, and learning alongside them. In my interview, I shared a portfolio of my work with teens, which showed that I could work with students and teachers to build lessons that integrated technology.

My job is going to change slightly this year. I’ll be housed in the library, still as a member of the technology department, with some opportunities to work in a more traditional librarian capacity, helping middle- and upper-school students with information literacy, research, and connecting them to fiction materials. I’ve had to teach myself a lot; if I’d gone straight into the library, I could have fallen back on what I did before. But because I’m in a totally different role, I have to teach myself tons.

What are some of the things you had to learn?

I threw myself into the job. I spent a lot of time at the beginning looking for resources. Lorri Carroll, Hamden’s Director of Technology and Information Services, sent me a lot of resources, activities, and blog posts that got me through the first weeks. And I depended heavily on the successes of others who were willing to share.

I would glom onto one or two technologies at a time, things that I was comfortable with, like blogging. So I talked to a few teachers about getting their students blogging, which was fun. Then Lorri and I talked about how we wanted to encourage some teachers to rethink their PowerPoint assignments, so I talked to a few teachers about VoiceThread. Then I became familiar with Glogster and introduced certain teachers to that. It was very trial-and-error at the beginning.

I would glom onto one or two technologies at a time, things that I was comfortable with, like blogging. So I talked to a few teachers about getting their students blogging, which was fun. Then Lorri and I talked about how we wanted to encourage some teachers to rethink their PowerPoint assignments, so I talked to a few teachers about VoiceThread. Then I became familiar with Glogster and introduced certain teachers to that. It was very trial-and-error at the beginning.

When you teach students how to use something a few times, you start to learn how to use it yourself. So at first, I was learning new technologies and flying by the seat of my pants. As I got more comfortable, I began looking at teachers’ curricula. My goal was to try to locate the right tool for an existing lesson, rather than find a lesson that would work for a particular tool. I would find classes that were doing research projects, for example, and ask if I could teach students about evaluating websites or creating citations with NoodleTools.

You’re very active on Twitter.

Twitter is amazing for professional development. There are two blogs that I read constantly: “iLearn Technology” by Kelly Tenkely and “Free Tech for Teachers” by Richard Byrne. The great thing about these two blogs is that you can search by subject, so you can instantly get a ton of ideas.

That said, I’m starting to build up my own toolbox. Right now I have a “collection” of tools like Glogster, VoiceThread, Audacity, and LiveBinders. While these are my go-to applications, I still have to think carefully about which one works best for a particular project and what teachers will be comfortable using. Some technologies are easier to sell than others.

Blogging is appealing to many of them because the benefits are so clear. If they’re leading classroom discussions, then they can extend those conversations beyond class with a blog. Blogging builds writing skills, encourages peer review, and allows students to share with an audience greater than their peers. Teachers just need help setting up blogs for their students and teaching them about online safety and etiquette, which is where I come in.

How do you make connections with teachers and help them understand the value of technology?

First, you reach out to your allies. Even if you’re new to a job, you see pretty quickly who’s open to using technology. Then it’s just a matter of asking teachers what projects their students are working on or what topics they’re introducing. After a few successes, word gets out. They’ll tell their colleagues that you’re collaborating on a project. That peer stamp of approval makes a big difference.

Then you reach out to the people who aren’t immediately buying in. It’s hard; you have to be tenacious. You can talk to them at faculty meetings or send them resources.

I created a blog this year, a take-off on Helene Blowers’s “23 Things” called “19 Things for Hamden Hall.” It ran for six weeks and the tools were grouped into topics like sharing, collaborating, writing—ones that I thought would interest teachers. I was really pleased with the response. Most participants weren’t seasoned technology users; in fact, many of them were downright nervous. I worked one-on-one with them as they made their way through the program, which definitely strengthened our relationship. Others were more comfortable but were learning about new resources nonetheless. As a result, I’ve been able to plan more with those teachers, and many of them are developing projects on their own, which is awesome. One fifth-grade teacher set up a wiki for her students after reading about it on the blog and loved it.

How do you help teachers connect technology to learning goals?

Almost from the beginning, teachers started asking me hard questions about why technology belongs in the educational experience and, at first, I wasn’t great at coming up with answers. I started looking at the major skills we want our students to leave our school with—skills like communication, collaboration, and evaluation of information. That made it easier to justify new technology. In fourth grade, for example, we used ToonDoo to create cartoons about a geographical region they were studying. At first glance, it might look like the students were just having fun, but they really had to work to identify the essential information in their research in order to express their ideas in a limited space. Once you observe that kind of learning process, you see that there are many layers that add to and support the classroom experience.

A huge challenge has been the inevitable technology glitches—computers that won’t turn on, downed sites. We need to teach faculty how to troubleshoot, but in the meantime, this stuff can really derail progress. At a certain point, you just have to be there and help teachers identify ways to prevent problems from recurring.

I’ve tried to share successful projects in order to show the faculty what’s possible. Sometimes teachers see those examples and think to themselves, “I can’t do that.” So it’s important to send the message that things don’t always go perfectly; we’re learning together.

Much of this process is personality driven. If you’re empathetic, supportive, and friendly, and you follow through on your promises, then people are more likely to want to work with you. Teachers can get embarrassed when they don’t know how to do something. I reassure them that their strength is in the fact that they want to learn. In a position like mine, you have to be open and share your knowledge, instead of sitting as the keeper of information. The point is to empower people, not to make them have to come to you.

How do you know if what you’re doing works?

I don’t evaluate projects’ success as often as I should, but it’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot. As I said, teachers will send me their students’ finished work. So I can look at all of the seventh-grade blogs, for example, and see what they’ve done or if there’s a common challenge our students had. Did they all forget to cite their sources or have trouble uploading videos? I’ve also started to get student feedback. I taught a Wikipedia unit to sixth graders last year where they learned about the anatomy of an entry, how the site works, red flags to look for in an article, etc. After the unit, I asked the students to write down their thoughts, which was really illuminating. I should have asked for feedback before the lesson started—I’ll do that this year.

Technology projects should be an extension of the classroom curriculum, and therefore students’ work should be assessed either by the teacher alone or jointly by the teacher and myself. For example, this year’s fifth graders will create PowerPoints on American Revolutionary War figures. That will be a part of their social studies work that extends into the technology classroom, and the teacher will grade their final work. I can help her with the technical piece if she would like, to help assess their skills, but I won’t assess them on the content since that’s not my knowledge area.

I do take detailed notes on lessons I teach in each grade, and I hope that I can learn from them.

What’s your dream relationship with the teachers you work with?

What’s your dream relationship with the teachers you work with?

I want teachers to feel empowered to develop projects on their own and for them to know where to find information about technology. That way, the genesis of the idea comes from them and then we plan the project together, build a rubric, and so on. Now we’re about halfway there; a teacher develops a project and they ask me to teach their students how to use a particular piece of technology, and then I’m done. I don’t see the outcomes, I don’t have any input on the timing or on the rubric. Sometimes, in the middle of teaching, one of us might realize that there’s an element missing or the timing’s off—all that might be prevented through planning. So co-planning a project from beginning to end would be ideal. Like I said, it’s close—the teachers are empowered to develop the idea—but we’re cooperating, not collaborating.

What are the barriers you face?

The number-one thing I hear from faculty? They don’t have time to learn about new technologies. What I tried to accomplish with the “19 Things” blog was to give teachers professional development on demand. When teachers had 15 minutes to spare after dinner or during a quick break during school, they could learn about a tool that I’d vetted for them.

I also hold “Tech Bytes” sessions. In these weekly 15-minute meetings, I answer teachers’ questions, which can be as simple as how to add and format images in Word. Some teachers use the time to review what they’re doing with their students for the next month. Then I can share what I think might fit in with what they’re planning.

Some teachers are afraid of breaking the technology or looking bad. One teacher was afraid of commenting on “19 Things” for fear of saying the wrong thing. I tried to reassure her, adding that the more she commented, the more comfortable she’d be. If someone isn’t used to blogging, it’s scary to put their ideas out there for everyone to read. Those of us who work with technology often fall into that trap—we’re comfortable with it, so we don’t understand why other people aren’t. Just because I know how to use something doesn’t mean someone else will.

Money can be a barrier, too. But a lot of what we’re using is free or cheap. I’m not telling teachers that they have to buy iPads for their students. We’re certainly conscientious about what we spend money on, but educational technology products are often not expensive. It’s not like being in a library, where you’re responsible for materials, programs, staffing, supplies, and more. I’ve bought subscriptions to a few websites at a minimal cost. We’re not really buying software anymore; all of these resources are Web-based.

What are the similarities and differences between being a tech coordinator and a school librarian?

A huge similarity is the emphasis on information literacy. I’m still teaching students how to find, use, and analyze information online. The same goes for digital citizenship, which is built into our technology plan. I’m still teaching research skills, but instead of print encyclopedias I show them how to use World Book Online and Wikipedia. I still talk about books. Some middle-school teachers learned that I had been a teen librarian, and they asked me to recommend books to their students. This year I’ll be doing even more of that, building up and promoting the young adult collection.

I taught a research and writing class when I was a school librarian, and I’m still in the classroom. I do miss the luxury of having a whole semester to teach a class as opposed to two days, though. This year I’m going to be working more with middle- and upper-school faculty and students to promote library resources and to explicitly build research skills.

I’m experiencing the same challenge that I felt as a school librarian, which is that when you’re not a classroom teacher, it takes longer to develop relationships with your students. Despite that, I’ve formed some amazing connections with my lower-school students, and I expect to do the same the more I get into the middle- and upper-school classes. I did a huge video project with the entire middle school this year and fell in love with every student. I feel much more visible to them, too.

I’m not a department head like I used to be. I don’t manage anyone or control a budget. I meet every week with the technology department, but not as an administrator or manager. Right now I’m on the frontlines. I’ve never been so on the frontlines before.

Do you feel like you’re a librarian regardless of your title?

Yes. That’s a realization I’ve come to. At the beginning of the year, I tried to make myself different than a librarian. Then as I got more comfortable in the work, I realized I shouldn’t try to hide my skills and background. Those are my strengths, and they connect to what I’m doing, so I refocused. That’s when I realized this job is no different from what I’ve done as a librarian.

But as a librarian I didn’t have faculty coming to me as much. For better or worse, it seems that the technology title makes people think I’m an expert on the topic more than the librarian title has. It’s the reputation of “librarian” that’s extremely frustrating. Now it’s easier to get people to trust my opinion on technology, which enables me to do more than I could as a librarian. So it boils down to: there’s more volume, a different title, and I don’t work in the library. (This year I’ll have my workspace in the library, but I’m still not a librarian by title.)

Are you the model of the librarian of the future?

Once you remove yourself from the physical constraints of the library, you have more freedom, because you aren’t limited by the title and the expectations of the job. If you get out of your library and take your knowledge everywhere, then you become a resource—no longer the keeper of a physical space or objects. You can focus on the most important skills that students need. You can take a fresh look at your curriculum and decide what’s really important for your students to experience. I don’t have to figure out if my educational goals fit into being a librarian or not, but rather, do they fit into the mission of the school as a whole?

It’s not that I eschew being a librarian now, it’s that the skills librarians need to focus on are changing, and I have an amazing opportunity to hone those skills, a chance I might not have were I still a traditional librarian. My job now is to get students and faculty excited about learning, and that’s pretty amazing.

About the author: Linda W. Braun (lbraun@leonline.com) is project management and consulting coordinator for LEO, a library consulting firm.

This month’s editorial considers Sarah Ludwig’s career path. View it on SLJ.com.

Photographs by Richard Freeda

[NOTE: This comment was deleted at Ms. Trevizo’s request.]

Wow…debatable topic…

Technology is part of the library

Should technology have been implemented before?

How is the new job working?

Kudos to her for finding her niche….

Technology is growing so much!

Maybe a tech journal should have this……

Here is to the new era of technology

This is a controversial issue since librarians are now having to defend their jobs.

So, should librarians now change their title?

I am confused.

What will come of the position now becuase of her experience.

Maybe it does belong in a tech magazine……

Very interesting

Good luck to her

As an educator and librarian, I’m disappointed to see the School Library Journal feature a person who is no longer a librarian. Sarah obviously chose to pursue a different career because librarianship was not her forte. Ironically, she did not realize (nor does School Library Journal, apparently) that technology is only one aspect of a multi-faceted LMS position. Obviously, anyone who is researching will align themselves with instructional sites and library or internet resources in 2012. Yahoo was launched in 1994, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yahoo and Twitter in 2006, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twitter! We’ve been using online resources for years but librarianship requires a need to balance reading for pleasure as well as information which is promoted in a digital format by librarians.

Sarah alluded to being “BUSY” as a librarian with the physical constraints reference. I just wish she had done so in a manner that advocated for librarians as crucial instructional specialists as well. Every librarian struggles with their inability to be in two places at once. Within a busy library media center, there are multiple focuses, consequently, some librarianships have budgeting available to fund multiple media positions. “Larger libraries are often divided into departments staffed by both paraprofessionals and professional librarians.

• Circulation (or Access Services) – Handles user accounts and the loaning/returning and shelving of materials.

• Collection Development – Orders materials and maintains materials budgets.

• Reference – Staffs a reference desk answering questions from users (using structured reference interviews), instructing users, and developing library programming. Reference may be further broken down by user groups or materials; common collections are children’s literature, young adult literature, and genealogy materials.

• Technical Services – Works behind the scenes cataloging and processing new materials and weeding old materials.

• Stacks Maintenance – Re-shelves materials that have been returned to the library after patron use and shelves materials that have been processed by Technical Services. Stacks Maintenance also shelf reads the material in the stacks to ensure that it is in the correct library classification order.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Library

Do school libraries have this luxury? No. Librarians today are multi-tasking fiends that singly perform all of the above, teach information literacy skills, integrate technology skills and help students become viable societal life forms! Our luxury includes circulation 3-5 books per minute as well as 20 to 25 classes each week with a part-time aide. Since Sarah is currently working in a private school, we all know the differences that impact instruction with privatizing…smaller classrooms, choice of students, parent input, etc. Our state budget restraints are not a factor but it is ironic that they will be placing her to work within the library. Let’s face it, Sarah’s position is sounding better and better but she is not a replacement for librarians. Who’s going to do the work if everyone is just teaching the skill? The difference in Sarah’s current position is time…, librarians do everything she is currently doing as a tech coordinator but she now has the luxury of time to focus on the instruction.

The title, “Next Year’s Model, Sarah Ludwig left the library, became a tech coordinator, and forged a path to the future”…Is? Please! It’s her future she is forging. I’m happy she’s successful but let’s give credit where it is due! The path to technology in libraries was forged long ago by names such as Bill Gates, Steve Job, etc… Technological usage and research has been utilized and taught before Sarah was born. We’ve had computers and internet in libraries for 20 years! Perhaps Connecticut has not had them.

Sarah is the viable product of some academic staff or school. Who was her librarian?

I wanted to reply as soon as I read this article, but I didn’t want to insult Sarah. I see her as a young woman who is looking for her place in the world. Chances are that she will return to librarianship – in a public school. It sounds like her current job has the frustrations of librarianship with out the rewards – including the reward of a decent salary and some sort of retirement.

Instead, I think that Rebecca Miller should seriously rethink her role as the Editor-in-Chief of SLJ. Are you here to support us or to insult us? I found the article insulting, with its implication that pretty young librarians are what is needed to take us into the future. True, there are a few pretty young school librarians out there, but not too many. Even the newest school librarians seems a bit long in the tooth, though we’re all beautiful.