Rebecca Forth doesn’t want kids to simply play Minecraft, she wants them to design their own worlds in the virtual building game. They can do just that and learn the necessary coding skills in a program set to launch at the Healdsburg branch of the Sonoma County (CA) Library (SCL) in March 2014.

Rebecca Forth,

Sonoma County (CA) Library

“We don’t want them to just play the game,” says Forth, the assistant to the director of SCL. “We want to teach them to feel empowered to generate their own content.”

Fifteen students will be given the first opportunity to participate in the three-session, afterschool program, where they’ll be taught how to work mods: modifications that allow players to alter Minecraft, from making new blocks to creating new pieces.

Forth’s son and a friend recently tackled their own mod by adjusting dynamite sticks readily available in the Minecraft tool kit, making them 100 times more powerful.

A professional coder in the community will be working with students during the first session using Eclipse, a coding application for Java which shows students the lines of code as they work. Students will use laptops already in the library and connect to a server set up just for the program. While recoding explosives is far from their only focus — although likely a popular one—the ability to personalize a video game is something most children don’t feel equipped to undertake. And that’s something Forth hopes to change.

“We want to take them from consumption to creation,” she says. “We want to emphasize problem solving and teamwork.”

Every child knows the rules of imaginary play—there are none. Enter the world of online and video gaming and suddenly they realize there are rules and boundaries, despite the technicolor interface and pixelated details. Minecraft. in its basic form, allows users to build their own worlds, with certain limits.

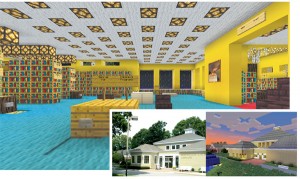

The Mattituck-Laurel Library in

New York – re-created in Minecraft.

Libraries across the country have latched onto the game, using it to attract students to the library. From building a version of their own branch, as Mattituck-Laurel library did last year, to launching Minecraft competitions—such as the one held last year at the Baxter Memorial Library in Vermont—the game is a powerful tool for librarians to use to engage their younger patrons.

Forth launched her program with help from a $6,000 grant from the California State Library and the Institute of Museum and Library Services to help cover costs, from the instructor’s fee to game licenses, as well as extra memory to make Minecraft run faster, she says. (The library is donating staff time.) She expects that most students who sign up will already be Minecraft enthusiasts. In fact, Forth has already fielded calls from parents interested in the program for their children.

As a pilot, the library will run assessments before, during, and after the first session to help inform two subsequent programs scheduled for Saturdays in April at the Rohnert Park branch, and then the first week on June at the Sebastopol branch. Forth also plans to build a tool kit, which she hopes other librarians will be able to employ to launch their own coding camps as well.

“One of the main goals is that this can be created at other libraries,” she says. “The idea is to create a turnkey program so all the documents are there, as well as curriculum and resources, so they can have what they need.”

Hello my name is Brandon Danielski and I would be very interested in any intern postilions that may be available for this project. If you need any interns with a basic knowledge of java I would be happy to apply. If interested please contact my email address at thisismypotpie@gmail.com. Thank you.

How can we bring this to Petaluma Library? The existing Java camps for mine craft are for the most part priced out of our financial reach!